18th Century Albany Street Names Part I

The Seven Years War (1756-1763) is considered by many historians to be the first truly ‘world war,’ with theaters in Europe, North and South America, Africa, India, and the Pacific. The War, which resulted in an overwhelming victory for Great Britain, was a turning point in the growth and development of British imperial ambitions. This was especially the case in North America, where the British gained control of all of Canada. The Seven Years War, known in the American colonies as the French and Indian War, had a profound effect on those same colonies and laid the groundwork in many ways for the drive for independence. The War has even been referred to as ‘The War that Made America.’

In 1764, when the Albany Common Council decided to lay out a grid plan of new streets and large blocks of land for development in the western reaches of the city, the Seven Years War, concluded barely a year prior, became an inspiration for the names the Council chose to give those new streets. The War had had a great impact on Albany, which had served as a jumping off point and military base for several expeditions against the French in Canada. The defeat of the French and their Indian allies had finally brought the prospect of peace for this frontier city, and the conclusion of the war would open the way for significant growth in Albany. Thus, it was even more fitting that the citizens of Albany would want to honor the heroes of that liberating conflict.

What follows are the names given by the Common Council to the new streets along with a brief explanation of the figures they were meant to honor. Going from north to south and then east to west. A map showing these streets is at the end of the article. The streets of this ancient city have many layers, but these street names are the foundations for what was to come.

Wall Street – the city’s northernmost street, named for its proximity to the stockade which encircled Albany for more then a hundred years. During the war, an effort was made to replace the log stockade with a more permanent stone wall. But shortly after the end of the war (before 1770), the entire stockade was removed.

Howe Street – named for Sir William Howe (1729-1814), participated in the capture of Quebec in 1759, and the capture of the French fortress at Louisbourg in 1758; during War of Independence, became Commander-in-Chief, British Land Forces in America until 1778.

Queen Street – any self-respecting British colonial town would have a series of names honoring the Crown and royal family. Such street names still exist in Alexandria, Virginia and York, Pennsylvania, among others.

King Street

Prince Street

Predeaux (or Prideaux) Street – named for General John Prideaux (1718-1759), an officer of the 55th Regiment of Foot who was killed at the Battle of Fort Niagara in 1759, by friendly fire, alas.

Quiter Street – I have not been able to find any person or thing this name references. Anyone have any ideas. Quiter is an English surname. Perhaps a local hero of the war?

Wolfe Street – named for Major General James Wolfe (1727-1759), ‘The Hero of Quebec” as he was hailed, for his role in the capture of that city in 1759, and where he was killed in action. He was considered a martyr of the British cause and became one of the most posthumously honored figures in British history.

Pitt Street – named for Sir William Pitt the Elder (1708-1788), leader of the House of Commons for the latter part of the war. Prior to the American Revolution, he was sympathetic with the Americans and was highly regarded in the Colonies.

Monckton Street – named for General Robert Monckton (1726-1782), he was second in command under General Wolfe at Quebec; oversaw the expulsion of the Arcadians from Nova Scotia; captured Martinique in 1762; was Governor of New York from 1763 to 1765.

And from east to west …

Duke Street

Hawke Street – named for Admiral Edward Hawke (1705-1781), commander of the Western Squadron during the Seven Years War; his most notable victory was at the Battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759, which thwarted a French attempt to invade Britain.

Boscawen Street – named for Admiral Edward Boscawen (1711-1761), he fought the French and Spanish in the War of Jenkin’s Ear and the War of Austrian Succession; during the Seven Years War, was second in command to Admiral Hawke during the capture of Louisbourg in 1758, and in 1759 won a decisive victory over the French at the Battle of Lagos (near Portugal). He signed the order of execution for the luckless Admiral John Byng for his failure to defend Minorca.

Warren Street – named for Admiral Sir Peter Warren (1703-1752), commanded British fleet during capture of French fortress at Louisbourg in 1745 (the first time); purchased large amounts of land along the Mohawk; invited his nephew Sir William Johnson to manage his lands, but subsequently disinherited him. Related by marriage to the DeLanceys of New York.

Johnson Street – named for Sir William Johnson (1715-1774), was made Superintendant of Indian Affairs for the northern colonies in 1754, but had spent years in a similar role for the New York colony. Led Indian and colonial militia forces against the French in the Seven Years War, and later in the American Revolution. The Battle of Lake George was a notable victory.

Gage Street – named for General Thomas Gage (1718-1787), served alongside George Washington at the disastrous Battle of the Monongahela in 1755; married Margaret Kemble, a descendant of the Schuyler family, in Albany prior to the Battle of Carillon in 1758, which was a significant British defeat; in 1763, became Commander of British Forces in America, a position he held until 1775 after his poor performance at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Schenectade Street – presumably the route to the town of Schenectady

Schoharie Street – (just off map) the route to Schoharie

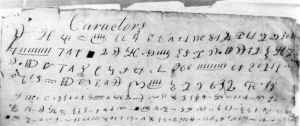

Below is the 1790 map which shows street names adopted in 1790 (more on that later) with the earlier names described above in red. Click the map twice to get a full-sized version.