This April 26 and 27 marked the 150th anniversary of the passage of Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train through Albany, en route to his final resting place in Springfield, Illinois. Many have written on this portion of Lincoln’s final journey (as many have written on every aspect of the 16th president’s life, death and burial), but I’m going to mainly present what was reported by Albany’s leading newspapers of the day, the Albany Evening Journal and the Albany Argus, with some other supplemental materials, according to my own particular (and peculiar) interests.

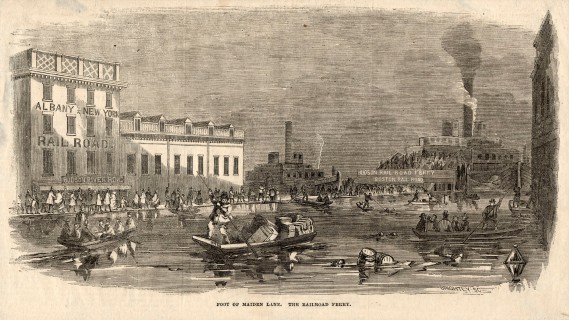

The visit of Lincoln’s mortal remains to Albany was unusual in that it involved a night-time arrival. The timetable for what was officially designated the ‘Lincoln Special’ called for the pilot locomotive to arrive on Tuesday, April 26th, at 10:55 p.m. at the Hudson River Rail Road depot in East Albany. In anticipation of its arrival, the officers and members of both houses of the Legislature gathered cross the river, in the Capitol’s Assembly Chamber at 10:00 pm. They were then escorted by three companies of New York State militia to the Hudson River RR ferry landing at the foot of Maiden Lane. Crowds had already filled State Street as the dignitaries made their way down to the waterfront.

On their arrival at the ferry landing, the presiding officers of the Legislature, together with the military escort, the members of the Albany Common Council, and members of the Committee on Arrangements, took a ferry across the Hudson to the East Albany station. A crowd of people from that side of the Hudson was also awaiting the President’s arrival. The pilot locomotive, the Hudson River RR’s Constitution, arrived about fifteen minutes late, giving the signal that the Presidential train would be following in ten minutes. The train of nine cars was pulled by the Hudson River RR locomotive Union (appropriately enough – it was the same engine that took Lincoln from Albany to New York City back in 1861 during his pre-Inauguration tour). On the front of the locomotive was a large portrait of Lincoln, covered in black bunting and illuminated with lanterns. The car containing the casket had only recently been built and had been originally intended as a special Presidential travelling car, a kind of ‘Air Force One’ for the Steam Age. This would be Lincoln’s only occasion to use it.

Upon the train’s arrival at the East Albany depot, Captain Harris Parr, Keeper of the State Arsenal in Albany commenced the firing of a minute gun – an artillery piece that would fire a blank charge every minute until Lincoln’s body arrived at the Capitol. This was also the signal for Albany’s many church bells to begin tolling. As word of the arrival spread, the crowds along State Street grew.

Members of the military escort removed the coffin from the train car and placed it on the hearse, drawn by four grey horses, which carried the remains to the ferry. The civilian and military escort accompanying the train, in all more than one hundred passengers, also got on board the ferry. The Evening Journal gave a moving description of that short trip across the Hudson:

“The hush of death prevailed on the ferryboat, as it crossed the river. The great chieftain, who had conquered the enemies of Union and Freedom, in the very hour of victory had been called to stand among the enshrined departed, to receive the full rewards which were awaiting the accomplishment of his glorious mission – and there, on that boat, civilians and chieftains, legislators and people, governors and governed, alike stood in mute awe around his cold remains.”

On the ferry’s arrival at the Maiden Lane landing, a procession quickly formed. A detachment of police in advance, followed by a drum corps of boys, then by Schreiber’s and Eastman’s College bands. The three militia companies (including the Albany Zouave Cadets, who were then designated Company A, 10th Regiment New York State National Guard) under the command of Gen. John F. Rathbone (cousin of Maj. Henry Rathbone) followed. Then came the hearse with its guard of honor. Behind came the Common Council, State officers, and the Legislature, all flanked by 100 firemen carrying torches. Additional light would have been provided by the many mourning displays in office and shop windows, many of which were illuminated for the occasion. Despite the huge crowds, already unusual for such a late hour, all remarked on the profound silence that prevailed during that midnight funeral procession.

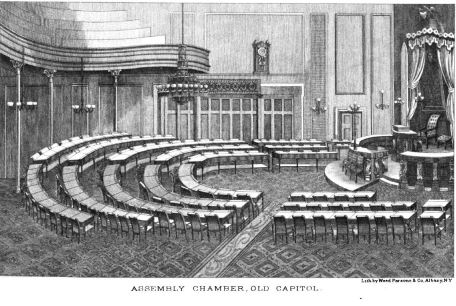

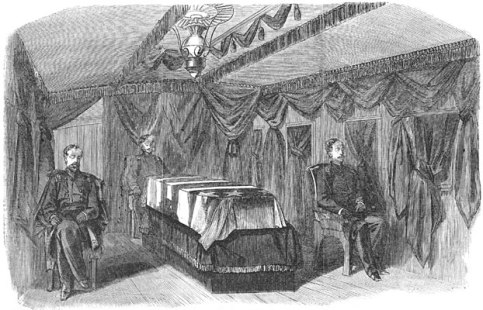

At the top of State Street, the coffin was removed from the hearse and carried through the front gate of the Capitol park on Eagle Street and on into the Capitol itself and the Assembly Chamber. The Chamber had been specially prepared to receive the remains. All the desks and chairs had been removed and a large dais, draped with mournful bunting, was erected in the center of the room. Over the Speaker’s chair was draped a banner with a quote from Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address: “I have an oath registered in Heaven to preserve, protect and defend the Government.” The Chamber had been decorated by B.W. Wooster, a popular Albany upholsterer and undertaker!

The Guard of Honor and members of the Veteran Reserve Corps (disabled veterans who were still capable of limited service) took their places around the dais while the embalmer and undertaker prepared Lincoln’s body for viewing. The Guard of Honor consisted of a group of six senior officers, changed every three hours. Gen. Rathbone was the senior officer for the first watch. Col. Frederick Townsend was senior officer for the fourth watch. When all was ready, the militia companies took up positions around the Capitol and its environs, the Capitol doors were opened, and the mourners were admitted to pay their respects. It was about 1:15 in the morning.

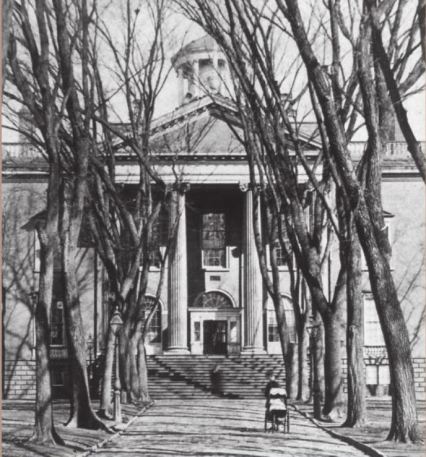

Two double file lines, four abreast, were formed which passed through the Eagle Street gate, up the front steps to the portico, and on into the Assembly Chamber. The line split, passing either side of the dais, the one line leaving by the north door, the other by the south door of the Capitol, then through the gates to either State Street or Washington Street. The line extended all the way down State Street, turning northward up Broadway. All throughout the night, the procession of mourners would continue, passing the President’s coffin at an estimated rate of 60 per minute. The huge numbers of mourners in every city had come as something of a surprise to organizers. One historian has written: “The pushing and hauling of so many people straining to get in at that unusual hour and for the somber purpose was wholly unexpected. Police and militia were present in small details only.”

The civilian and military guests accompanying the Lincoln Special were escorted to the Delavan House and Congress Hall. The funeral party was said to be in a state of exhaustion, practically in a daze from the stunning crowds which had met them at every stop. The Illinois delegation, overwhelmed by it all, sent a member on ahead to warn the people of Springfield to get ready. All that previous afternoon, crowds had arrived by train and boat, from all over New York and New England, far outstripping the city’s ability to accommodate them. Hundreds milled about the street all night, having no place to stay. Some were provided shelter in a schoolhouse. Many restaurants remained open all night to provide for the masses of strangers.

The railroad men would also have been busy that night. Getting the President’s train from the Hudson River RR depot in East Albany to the New York Central RR tracks in Albany required a series of complex maneuvers in the days before the Livingston Avenue bridge, which was completed the following year. The train would have continued north on the Hudson River RR tracks to Troy. Perhaps in Troy, it would have switched engines and continued on the tracks of the Troy & Schenectady RR, crossing over the Green Island railroad bridge to West Troy, switching to the Albany & Rutland RR tracks, then proceeding south to Albany. At Albany, it was switched to the tracks of the New York Central and fitted out with a NYCRR locomotive and pilot engine in time for the continuation of the ‘Lincoln Special’ westward.

One passenger of the ‘Lincoln Special’ who did not disembark the train was President Lincoln’s deceased son Willie, who had died of typhoid fever in 1862. Willie’s remains had been disinterred and placed on the train, in a plain white casket, so that he might be buried with his father in Springfield. His body was kept in the same compartment of the hearse car that carried the elder Lincoln’s remains.

The day was clear and bright, pleasantly warm – a contrast to the rains of the day before. All through the morning the anxious crowds kept coming without let up. With such crowds, some chaos was inevitable. One eyewitness, in describing the scene at the narrow gate outside the Capitol, on Eagle Street, through which all the mourners had to pass, noted: “[We] found there a crush and a crowd almost uncontrollable in its impatience after so long a wait. The gateway was not wide, and the police could not prevent frequent jams and small panics. Women screamed and fainted, hats and articles of wearing apparel were lost, and at times men fought for a place.” And then, there were the pickpockets. At least one visitor from a rural area lost $100 in U.S. bonds to a pickpocket.

But far more remarked upon was the silence that prevailed. The Argus described it aptly: “Aside from the slow tread of the procession, not a sound was to be heard in the streets. Every place of business remained closed, not a vehicle was to be seen passing through the streets, and never upon a Sabbath morning did the city present a stillness so complete.” “Many were in tears and conversation was carried on in hushed tones,” said another eyewitness.

Controversy existed then and now over what the mourners would have seen of Lincoln. The science of embalming was still in its infancy and the task before the official embalmers was daunting – preserve a body (and especially a face) for a two week trip involving multiple open air viewings over many hours and a long and bumpy train ride. No one had ever done that before. In Philadelphia, eyewitnesses found him looking “quite natural.” So did the Philadelphia Inquirer, which observed “a natural, placid, peaceful expression.” But after the 23 hour viewing marathon in New York City, doubts began to arise. The New York Times reported that his face had changed several shades darker than it had been and that, with his jaw dropping and teeth visible, “it was not a pleasant sight.” In Albany, embalmer Charles Brown and undertaker Frank Sands handed a firm denial to the press: “No perceptible change has taken place in the body of the late President since it left Washington.” But reporters in Albany noted that Lincoln was “evidently growing yet darker in spite of the chemicals used as preservatives.” One Albany eyewitness, who had been a child at the time remembered “in three or four places, perhaps, small dark-blue spots.” But most ordinary citizens seemed to see the man rather than the blemishes. Louise Coffin Smith of Troy recalled “The tired worn face of our President had a look of peace.” She also remembered “an old colored woman [who] attempted to kiss him, saying between her sobs, ‘We have lost our best friend.’”

At 10 a.m., the members of the Legislature and State officers assembled in the State Library, and proceeded in a body to view the remains. Finally, at noon, the doors of the Capitol were closed and preparations for the procession to the train were begun. There was still a line of many thousands extending all the way to Broadway when the viewing was ended. Estimates were that more than 50,000 had viewed Lincoln’s body.

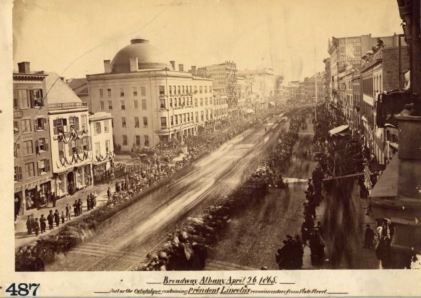

The procession began at about 2:00 p.m. Detachments of police led the cortege, followed by General Rathbone and his brigade – the three regiments of New York National Guard, the 10th and 25th regiments from Albany, the 24th Regiment from Troy, and the Troy Light Horse Artillery Battery. The hearse followed, pulled this time by six white horses. Then came the State and local officials, civic associations – St. Andrew’s Society, Hibernians, Fenians, Masons, Odd Fellows, Druids, German Turnvereins – the ever-present Albany Burgesses Corps, followed by firemen from Albany and surrounding communities. The procession wended its way up Washington Avenue, south along Dove Street, then back toward downtown on State Street.

Church bells tolled as the solemn procession moved through the city. It moved quickly. Though several thousands marched, it took only 30 minutes for it to pass a given point, in contrast to the four hours required for the procession in New York City. 80,000 were said to be lining the route of the procession. Four bands accompanied the marchers, playing, it was reported, “Love Not,” “Auld Lang Syne,” and “Come and Let Us Worship,” and other funereal songs. All marchers were on foot, including the governor and mayor. No carriages, banners or floats were permitted. Even more remarkably, there was not a single speech given by anyone.

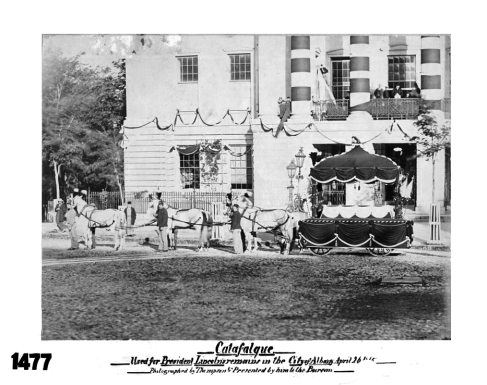

At the foot of State Street, the cortege turned up Broadway and went, not to the NY Central depot, but to a place known as ‘the Crossing,’ where the railroad tracks intersected Broadway, just beyond Lumber Street (later Livingston Avenue). There the ‘Lincoln Special’ was waiting, already under steam. The Edward H. Jones was the locomotive, with the Chauncey Vibbard serving as the pilot engine. The elaborate hearse car had itself been an attraction during the day, with thousands of people passing through it.1 Without ceremony, Lincoln’s coffin was placed on board. It took another fifteen minutes for the large military and civilian escort to board the cars. And then, right on schedule, at 4:00 in the afternoon, the ‘Lincoln Special’ steamed out of the capital city of the Empire State and on toward Lincoln’s final resting place.

1 The hearse car, which had been originally built for the living President, was variously described as being of black, brown, chocolate, maroon, or red in color. In 2013, scientific analysis of paint chips from a surviving window frame from the car showed the color to have been a deep maroon – four parts black and one part red.

I’m grateful to the Albany Group Archive on Flickr for some of the photos. Also to Fultonhistory.com for the relevant newspaper pages. Additional information came from Mrlincolnandnewyork.org , Abrahamlincolnsclassroom.org , and from an article on Lincoln’s body, found in Slate.com by Richard Wightman Fox.

What was the source of the picture at the top of the Lincoln blog article?

LikeLike

I did not realize this when I posted the photo, but it is actually a recreation by 3D illustrator Ray Downing. But it is based on the one known photo of Lincoln lying in state in New York City.

LikeLike

How can a close up of Lincoln’s body in the coffin look so clear from the blurry photo it was enlarged from?

LikeLike

It is a 3D recreation by illustrator Ray Downing, based on the one known photograph of Lincoln lying in state.

LikeLike